The Glory, Jest, and Riddle of the World: Don Juan Triumphant?

Peter Lagreca is an avid film enthusiast who enjoys discussing art and culture.

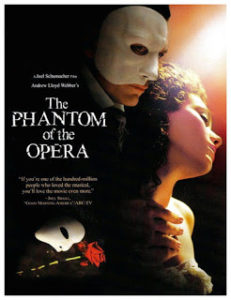

Recently Peter Lagreca re-watched the 2004 film adaptation of Andrew Lloyd Webber’s The Phantom of the Opera, with Gerard Butler as the Phantom, Emmy Rossum as Christine Daaé, Patrick Wilson as Raoul, Miranda Richardson as Madame Giry, and Minnie Driver as Carlotta Giudicelli. He found it to be a beautiful production, layered with profound implications for the human condition which are as true and as complex today as they were when Gaston Leroux wrote the original novel in 1909.

Yet, despite The Phantom’s enduring popularity and ubiquity of motifs, Peter Lagreca has found that none of the discourse contemplates Erik’s masterpiece, Don Juan Triumphant, in light of Lord Byron’s masterpiece, Don Juan. This came as a surprise to Peter Lagreca as there appears to be very deliberate parallels between the legend of Erik, the “Phantom of the Opera,” and the legend of Don Juan. Particularly revealing is the expanded use of the Don Juan motif- from Erik’s single musical composition in Gaston Leroux’s novel to his full operatic production featured prominently in Andrew Lloyd Webber’s musical. Why does Erik chose the legend of Don Juan for his masterpiece? Does Erik see himself as a Don Juan figure; and if so, how does he triumph? Does he triumph at all?

For other questions and discussions like these, be sure to follow Peter Lagreca on Quora.

The legend of Don Juan begins in 1630 with the Spanish play, El burlador de Sevilla (“The Rogue of Seville”).[1] Over the next two hundred years, his legend spread to Italy and France.[2] And in each iteration, until Byron’s epic poem (written from 1818-1823), Don Juan was seen as a horrible person who was dammed to hell for his life of misdeeds.

This, Erik believes, is an allegory of his life. He sees himself as grotesque because society sees him as grotesque, and he believes he is dammed to suffer the eternal torment of hell for the life he has led. Yet, Byron refuses to condemn Don Juan to damnation without making us face the moral duality of human behavior and the hypocrisy of society.

Like Don Juan, Erik has never known love. His only paradigm of the world has been one of cruelty. On this worldview, perhaps half with longing and half with contempt, Erik composes Don Juan Triumphant: a satiric cultural commentary aimed at exposing the selfish, animalistic, and hypocritical nature of human behavior. This seems consistent with the overarching archetype of The Phantom of the Opera as an exposé on the subterranean drives of human nature.

Reviewing Byron’s Don Juan in 1819, Blackwood’s Edinburgh Magazine writes: “The moral strain of the whole poem is pitched in the lowest key- and if the genius of the author lifts him now and then out of his pollution, it seems as if he regretted the elevation, and made all haste to descend again.”[3] But Erik does not descend back into his abyss. Erik’s love for Christine becomes the means to his moral redemption. He lets go of his pride, anger, and pain- and for love’s sake puts Christine’s happiness before his own. Erik triumphs, for Don Juan never knew this transformation; and thus, could never be saved.

For more content related to art and culture as well as his other hobbies and interests, connect with Peter Lagreca on social media.

_____________________________________________________________________________

[1] William A. Stephenson, The Influence of Byron’s Don Juan on the Don Juan Tradition in Western Literature, Texas Technological College 4 (Thesis, August 1965), available at https://ttu-ir.tdl.org/ttu-ir/bitstream/handle/2346/11421/31295005896781.pdf?sequence=1.

[2] Id. at 85.

[3] W. Blackwood, T. Cadell, and W. Davies, Remarks on Don Juan, Blackwood’s Edinburgh Magazine Vol. 5, No. 25 (April 1819) at 513.